【协和医学杂志】女性甲状腺癌高发的病因研究进展

时间:2025-09-28 12:14:13 热度:37.1℃ 作者:网络

目前生殖系统以外的肿瘤在临床诊疗上基本无性别差异,但忽视性别对非生殖系统肿瘤的影响,尤其是甲状腺癌(TC),将阻碍对疾病的深层分析,并影响性别差异性治疗。甲状腺肿瘤是唯一女性发病率高于男性3~4倍的非生殖系统肿瘤[1],值得研究人员探究其性别差异,希望未来TC的性别差异因素可在临床诊疗中发挥作用。

甲状腺肿瘤是最常见的内分泌肿瘤[2],其病理类型分为分化型甲状腺癌(DTC)、未分化型甲状腺癌(ATC)和髓样癌(MTC),DTC又分为乳头状甲状腺癌(PTC)和滤泡状甲状腺癌(FTC)。DTC的发病率为90%左右,ATC的发病率为6%左右,MTC的发病率为4%左右[3];值得注意的是,在上述总体发病率中,女性发病率约占3/4[1]。因此,研究性别因素在TC发病中的影响,对于根据性别差异开展TC临床预防和治疗至关重要。

1 女性TC高发因素

研究显示,雌激素是女性TC高发的主要原因,其通过基因途径及非基因途径导致TC发生。女性比男性更易出现脂肪堆积,脂肪细胞促进炎症因子的释放,减少氨基肽酶N(APN),增加瘦素、芳香化酶的浓度,导致女性TC的发生率增高。此外,月经、生殖因素、避孕药、氧化-抗氧化系统失衡、X染色体等均可导致女性TC发病率高于男性。女性TC高发因素汇总详见表1。

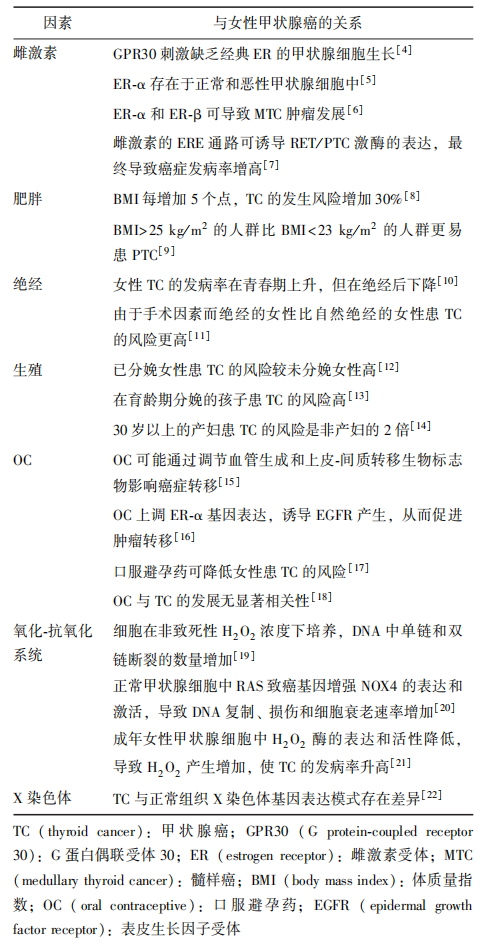

表1 女性TC高发因素汇总

1.1 雌激素受体

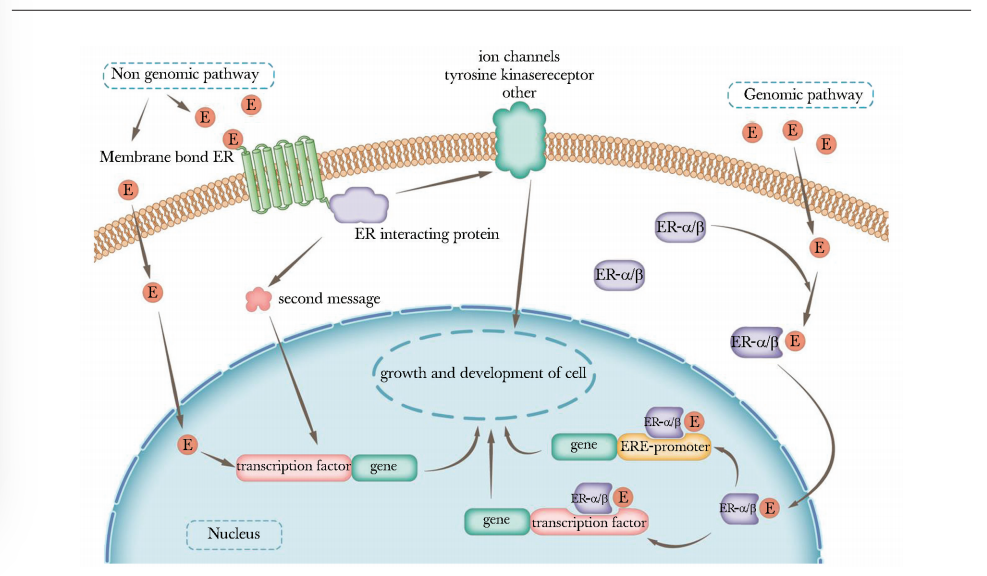

雌激素是一种类固醇激素,在调节人体生长发育、心血管、免疫等方面发挥重要作用。雌激素可通过基因组和非基因组途径对细胞产生作用。基因组途径是指雌激素需同其受体(ER)结合(主要受体为ER-α[4]和ER-β[23]),形成雌激素ER复合物,进入细胞,随后核易位,发生同二聚化或异二聚化,再同细胞核中的雌激素反应元件(ERE)结合[24],进而影响细胞生长及发展,此为雌激素作用于细胞的主要方式,称为ERE途径。非基因组途径是指雌激素与DNA结合的其他转录因子结合[25],或雌激素同细胞膜上的受体结合形成细胞膜结合复合物,进而启动相应的下游信号[26](图1)。

图1 雌激素作用于甲状腺细胞的信号通路图

non genomic pathway:非基因途径;membrane:细胞膜;second message:第二信使;transcription factor:转录因子;ion channel:离子通道;tyrosine kinase receptor:酪氨酸蛋白激酶受体;genomic pathway:基因途径;ERE-promoter:ERE启动子; E(estrogen):雌激素;gene:基因; nucleus:细胞核;ER:同表1

如在一些TC细胞系中,研究人员发现了一种新的G蛋白偶联受体(GPR 30),该受体是雌激素信号传导的非ERE途径之一,可刺激缺乏ER的甲状腺细胞生长[27],这种非基因组途径的作用速度较基因组途径更快。

男性和女性的甲状腺细胞中均存在ER,但值得注意的是女性的ER水平高于男性。ER-β在正常和恶性甲状腺细胞中均存在,有研究认为正常和恶性甲状腺细胞均表达ER-α[5],此为女性TC发病率高于男性的原因之一。总之,女性TC发病率高不仅与女性ER表达量高有关,且与女性体内雌激素高于男性密切相关,因雌激素可通过基因型和非基因型途径促进恶性甲状腺细胞的生长与发展。

研究发现,MTC中ER-α与ER-β的占比不同也将影响肿瘤的生长及发展,此研究还证实了ER-α与ER-β导致MTC发生发展的作用方式不同[6],其具体作用机制仍有待未来探索。除此之外,转染期间重排的RET/PTC(原癌基因酪氨酸蛋白激酶受体RET与PTC相关基因重排形成融合基因)是参与甲状腺肿瘤发生的癌基因,雌激素的ERE途径可诱导RET/PTC激酶表达,导致多种下游激酶信号通路磷酸化升高,从而使TC的发病率增加[7]。

此外,研究还发现雌激素具有促炎作用[28]。雌激素本身即可塑造许多失调的细胞和分子途径,导致非生殖系统细胞的增殖和癌症发生[29]。绝经期雌激素补充治疗可增加TC的发生风险[30],上述研究均支持女性TC发病率高与雌激素密不可分。

1.2 肥胖

肥胖主要由脂肪组织堆积引起,女性脂肪堆积量通常大于男性,即使是同样的脂肪堆积量,女性的脂肪氧化量低于男性,故女性较男性更易出现肥胖[31],这可能是女性TC发病率高于男性的主要因素之一。已有研究证实,肥胖与癌症的发生存在相关性,其中包括TC。研究发现,体质量指数(BMI)增加与TC发病率呈正相关,其每增加5个点,TC的发病风险可增加30%[8]。也有研究证实,BMI>25 kg/m2的人群患PTC的风险高于BMI<23 kg/m2的人群[9]。

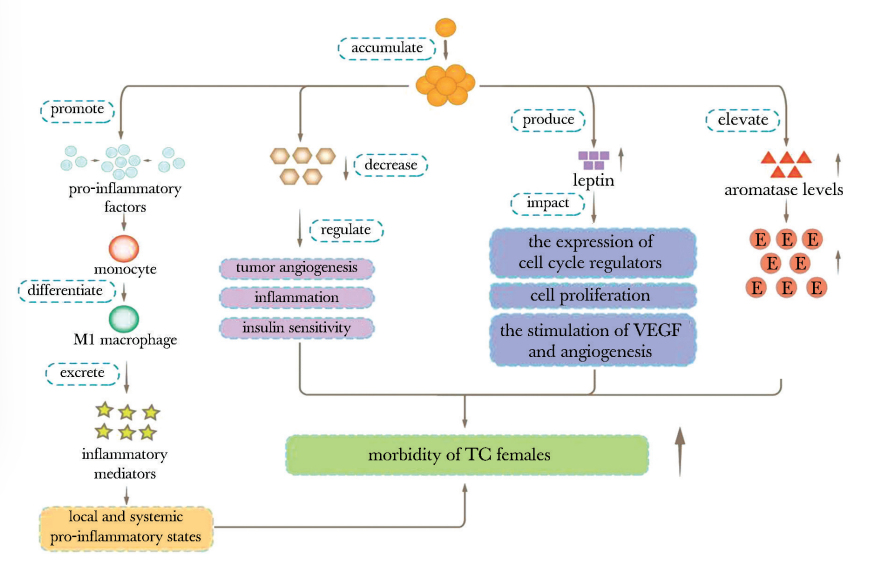

根据现有研究,脂肪组织导致肿瘤发生的机制可概括为以下方面。

促炎作用。过多的脂肪组织堆积使机体免疫系统失调,其特征为免疫细胞浸润和活化增加[32]。在肥胖症患者中,脂肪组织肥大加速促炎因子产生,进而导致单核细胞浸润并分化为促炎的M1巨噬细胞[33],这类巨噬细胞又可产生引发局部和全身促炎反应的炎症介质[34],造成炎症反应不断放大。

APN。APN通过调节肿瘤血管生成、炎症和胰岛素敏感性发挥作用,肥胖可导致脂肪细胞特异性因子APN减少。研究表明,APN水平较低与TC的发生存在相关性,尤其是女性群体[35]。

瘦素。瘦素主要由脂肪组织产生,其影响细胞周期调节因子的表达、细胞的增殖、血管内皮生长因子(VEGF)的刺激、血管的生成[36]。研究发现,在TC患者组织中瘦素及其受体表达增加[37],因此肥胖人群易患TC,尤其是脂肪组织堆积的女性。

芳香化酶。肥胖人群的芳香化酶浓度增加,致使雌激素浓度升高,而雌激素可通过多种途径促使TC发生[38]。因此,在肥胖和雌激素的双重作用下,女性TC的患病率较男性更高(图2)。

图2 脂肪组织的致癌作用图

pro-inflammatory factors:促炎症因子;monocyte:单核细胞;M1 macrophage:M1巨噬细胞;inflammatory mediators:炎症介质;tumor angiogenesis:肿瘤血管生成;insulin sensitivity:胰岛素敏感性;leptin:瘦素;the expression of cell cycle regulators:细胞周期调控因子表达;cell proliferation:细胞增殖;aromatase:芳香化酶;mobidity:发病率; VEGF(vascular endothelial growth factor):血管内皮生长因子; TC:同表1; E:同图1

1.3 生殖因素

1.3.1 绝经

研究发现,青春期女性TC发病率升高,绝经后女性TC发病率反而下降[10],绝经可能是女性TC发生的影响因素之一。但需注意的是,TC的发生与绝经状态也存在相关。研究发现,因手术因素导致绝经的女性比自然绝经的女性更易罹患TC[11]。但也有研究指出,绝经状态、初次生育年龄、初潮年龄、绝经年龄和TC的发病率无明显关联[11,39]。因此,绝经对于女性TC发病率的影响仍需更多研究验证,未来需开展更多研究进一步探索。

1.3.2 分娩

研究发现,相较于未分娩女性,分娩期女性患TC的风险更高[12];处在生育年龄的女性,TC的患病风险达最高点[13],且年龄>30岁的分娩期女性比非分娩期女性患TC的风险高2倍[14],分析其原因可能与人绒毛膜促性腺激素(hCG)刺激促甲状腺激素(TSH)和ER导致肿瘤细胞的侵袭性增加有关[40]。但并非不生育就可降低TC的发生风险,存在不孕问题的女性,其TC的患病风险也较高,因不孕不育可能由甲状腺疾病引发,也可能与不孕不育女性在服用生育药物期间对甲状腺的监测增加有关[41]。

1.3.3 口服避孕药

口服避孕药(OC)对女性不同系统癌症发生率的影响作用不同,如OC可降低女性子宫内膜异位症、胶质瘤、子宫内膜癌、结直肠癌、卵巢癌、食管腺癌和肾癌等疾病的发生率[42]。但OC又可增加女性乳腺癌、静脉血栓形成和缺血性卒中等疾病的发生风险[43]。关于OC对女性TC发病率的影响,研究发现OC可通过调节血管生成和上皮-间质转化(EMT)生物标志物,进而促进TC转移[15],原因之一是OC上调了ER-α基因表达,从而诱导EGFR的产生,进而促进肿瘤转移[16]。有趣的是,另有研究指出OC可降低女性患TC的风险[17],也有研究指出OC与TC的发生及发展无显著关联[18]。

目前,绝经、分娩、OC与女性TC发病率的相关研究较少,其具体作用机制有待研究进一步证实,未来需开展更多高质量的临床研究。

1.4 甲状腺细胞氧化-抗氧化系统

研究表明,TC的发生由细胞所受氧化环境所致,甲状腺细胞氧化-抗氧化系统失衡可能为女性甲状腺疾病高发的原因之一[44]。实验研究证实,在甲状腺疾病的发生过程中,过氧化氢(H2O2)含量增加及抗H2O2酶活性增强;此外,活性氧(ROS)可能与细胞成分(如脂质、蛋白质、DNA等)发生反应,导致自身免疫性甲状腺疾病,以上均说明ROS与甲状腺细胞的生长密切相关[45]。

研究发现,甲状腺细胞暴露于H2O2环境下,RET/PTC将发生重排;细胞在非致死的H2O2浓度下培养,DNA中单链和双链断裂数量增加[19],加入H2O2酶后可消除这种重排[46]。

烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸氧化酶4(NOX4)是一种还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸酶,可产生H2O2,NOX4的激活通常导致氧化还原反应失衡。研究发现,正常甲状腺细胞中RAS致癌基因可增加NOX4的表达和活化,刺激DNA复制率增加,导致DNA损伤,从而加速细胞衰老,可能为TC发生的原因之一[20]。

研究发现,成年女性甲状腺细胞中H2O2酶的表达和活性下降,导致H2O2生成增多[21],说明氧化-抗氧化系统失衡可能是女性TC患病率高于男性的原因。

1.5 X染色体

女性比男性多1条X染色体,理论上X染色体具有失活机制,可平衡两性之间的患癌差异,但研究发现15%的X染色体基因逃脱了失活机制,导致女性性X染色体具有双倍拷贝[47]。研究发现,X染色体上的一些基因在TC与正常组织中的表达模式存在差异[22],其中一种基因FOXP3,其多态性的AA和AC基因型在女性X染色体上出现的频率高于男性[48],这一发现从X染色体方面解释了TC发病率具有性别差异。未来需开展更多研究探索X染色体基因表达导致女性TC发病率高的机制。

2 小结与展望

雌激素和肥胖是导致女性TC高发的主要因素。雌激素通过ERE和非ERE机制在TC细胞的生长发育过程中发挥至关重要作用,其与肥胖、生殖等因素共同作用导致女性TC的发生。女性体内脂肪容易堆积,其通过释放促炎因子和增加雌激素浓度导致甲状腺细胞癌变。此外,研究表明,TC更常见于育龄期女性,绝经后女性的发病率下降。然而,非自然绝经女性的发病率增加,也有研究持不同观点,未来仍需开展更多研究加以验证。甲状腺细胞中氧化-抗氧化系统失衡可导致氧化物增加,其与女性TC呈正相关。X染色体的基因差异也可能是TC发病率出现性别差异的根本原因,未来需更多研究探索其分子机制。针对女性TC,期待今后开展更多研究探索其病因机制,为女性TC的治疗提供新思路和新方向。

参考文献

[1]Ferlay J S I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11[J]. International Journal of Cancer Journal International Du Cancer, 2015, 136(5): E359-E386.

[2]Kilfoy B A, Zheng T, Holford T R, et al. International patterns and trends in thyroid cancer incidence, 1973—2002[J]. Cancer causes & control: CCC, 2009, 20(5): 525-531.

[3]Prete A, Borges de Souza P, Censi S, et al. Update on Fundamental Mechanisms of Thyroid Cancer[J]. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 2020, 11: 102.

[4]Green S, Walter P, Greene G, et al. Cloning of the human oestrogen receptor cDNA[J]. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry, 1986, 24(1): 77-83.

[5]Vaiman M, Olevson Y, Habler L, et al. Diagnostic value of estrogen receptors in thyroid lesions[J]. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 2010, 16(7): BR203-207.

[6]Cho M A, Lee M K, Nam K H, et al. Expression and role of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in medullary thyroid carcinoma: different roles in cancer growth and apoptosis[J]. The Journal of Endocrinology, 2007, 195(2): 255-263.

[7]Wang C, Mayer J A, Mazumdar A, et al. The rearranged during transfection/papillary thyroid carcinoma tyrosine kinase is an estrogen-dependent gene required for the growth of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells[J]. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 2012, 133(2): 487-500.

[8]Schmid D, Ricci C, Behrens G, et al. Adiposity and risk of thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Obesity Reviews, 2015, 16(12): 1042-1054.

[9]Kim K N, Hwang Y, Kim K H, et al. Adolescent overweight and obesity and the risk of papillary thyroid cancer in adulthood: a large-scale case-control study[J]. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1): 5000.

[10]Tahboub R, Arafah B M. Sex steroids and the thyroid[J]. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2009, 23(6): 769-780.

[11]Zamora-Ros R, Rinaldi S, Biessy C, et al. Reproductive and menstrual factors and risk of differentiated thyroid carcinoma: the EPIC study[J]. International Journal of Cancer, 2015, 136(5): 1218-1227.

[12]Cao Y, Wang Z, Gu J, et al. Reproductive Factors but Not Hormonal Factors Associated with Thyroid Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis[J]. BioMed Research International, 2015, 2015: 103515.

[13]Sakoda L C, Horn-Ross P L. Reproductive and menstrual history and papillary thyroid cancer risk: the San Francisco Bay Area thyroid cancer study[J]. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 2002, 11(1): 51-57.

[14]Braganza M Z, Berrington de González A, Schonfeld S J, et al. Benign breast and gynecologic conditions, reproductive and hormonal factors, and risk of thyroid cancer[J]. Cancer Prevention Research (Philadelphia, Pa.), 2014, 7(4): 418-425.

[15]Dehghan M H, Ashrafi M R, Hedayati M, et al. Oral Contraceptive Steroids Promote Papillary Thyroid Cancer Metastasis by Targeting Angiogenesis and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition[J]. International Journal of Molecular and Cellular Medicine, 2021, 10(3): 219-226.

[16]Yamamoto Y, Moore R, Hess H A, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates 17alpha-ethynylestradiol causing hepatotoxi-city[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2006, 281(24): 16625-16631.

[17]Wu L, Zhu J. Linear reduction in thyroid cancer risk by oral contraceptive use: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies[J]. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 2015, 30(9): 2234-2240.

[18]Pham T M, Fujino Y, Mikami H, et al. Reproductive and menstrual factors and thyroid cancer among Japanese women: the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study[J]. Journal of Women's Health (2002), 2009, 18(3): 331-335.

[19]Driessens N, Versteyhe S, Ghaddhab C, et al. Hydrogen peroxide induces DNA single- and double-strand breaks in thyroid cells and is therefore a potential mutagen for this organ[J]. Endocrine-Related Cancer, 2009, 16(3): 845-856.

[20]Weyemi U, Dupuy C. The emerging role of ROS-generating NADPH oxidase NOX4 in DNA-damage responses[J]. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, 2012, 751(2): 77-81.

[21]Fortunato R S, Braga W M O, Ortenzi V H, et al. Sexual dimorphism of thyroid reactive oxygen species production due to higher NADPH oxidase 4 expression in female thyroid glands[J]. Thyroid: Official Journal of the American Thyroid Association, 2013, 23(1): 111-119.

[22]Achilla C, Papavramidis T, Angelis L, et al. The Implication of X-Linked Genetic Polymorphisms in Susceptibility and Sexual Dimorphism of Cancer.[J]. Anticancer research, 2022, 42(5): 2261-2276.

[23]Kuiper G G, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, et al. Cloning of a novel receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1996, 93(12): 5925-5930.

[24]Nilsson S, Mäkelä S, Treuter E, et al. Mechanisms of estrogen action[J]. Physiological Reviews, 2001, 81(4): 1535-1565.

[25]Paech K, Webb P, Kuiper G G, et al. Differential ligand activation of estrogen receptors ERalpha and ERbeta at AP1 sites[J]. Science (New York, N.Y.), 1997, 277(5331): 1508-1510.

[26]Hammes S R, Levin E R. Extranuclear steroid receptors: nature and actions[J]. Endocrine Reviews, 2007, 28(7): 726-741.

[27]Vivacqua A, Bonofiglio D, Albanito L, et al. 17β-Estradiol, Genistein, and 4-Hydroxytamoxifen Induce the Proliferation of Thyroid Cancer Cells through the G Protein-Coupled Receptor GPR30[J]. Molecular Pharmacology, 2006, 70(4): 1414-1423.

[28]Luo S D, Chiu T J, Chen W C, et al. Sex Differences in Otolaryngology: Focus on the Emerging Role of Estrogens in Inflammatory and Pro-Resolving Responses[J]. International journal of molecular sciences, 2021, 22(16):8768.

[29]Costa A R, Lança de Oliveira M, Cruz I, et al. The Sex Bias of Cancer.[J]. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM, 2020, 31(10): 785-799.

[30]Zhang G Q, Chen J L, Luo Y, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and women's health: An umbrella review.[J]. PLoS medicine, 2021, 18(8): e1003731.

[31]Toth M J, Gardner A W, Arciero P J, et al. Gender differences in fat oxidation and sympathetic nervous system activity at rest and during submaximal exercise in older individuals[J]. Clinical Science (London, England: 1979), 1998, 95(1): 59-66.

[32]Kawai T, Autieri M V, Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity[J]. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 2021, 320(3): C375-C391.

[33]Shoelson S E, Lee J, Goldfine A B. Inflammation and insulin resistance[J]. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2006, 116(7): 1793-1801.

[34]Haase J, Weyer U, Immig K, et al. Local proliferation of macrophages in adipose tissue during obesity-induced inflammation[J]. Diabetologia, 2014, 57(3): 562-571.

[35]Dossus L, Franceschi S, Biessy C, et al. Adipokines and inflammation markers and risk of differentiated thyroid carcinoma: The EPIC study[J]. International Journal of Cancer, 2018, 142(7): 1332-1342.

[36]Lin T C, Huang K W, Liu C W, et al. Leptin signaling axis specifically associates with clinical prognosis and is multifunctional in regulating cancer progression[J]. Oncotarget, 2018, 9(24): 17210-17219.

[37]Zhang G A, Hou S, Han S, et al. Clinicopathological implications of leptin and leptin receptor expression in papillary thyroid cancer[J]. Oncology Letters, 2013, 5(3): 797-800.

[38]Leeners B, Geary N, Tobler P N, et al. Ovarian hormones and obesity[J]. Human Reproduction Update, 2017, 23(3): 300-321.

[39]Kabat G C, Kim M Y, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Men-strual and reproductive factors, exogenous hormone use, and risk of thyroid carcinoma in postmenopausal women[J]. Cancer causes & control: CCC, 2012, 23(12): 2031-2040.

[40]Vannucchi G, Perrino M, Rossi S, et al. Clinical and molecular features of differentiated thyroid cancer diagnosed during pregnancy[J]. Eur J Endocrinol, 2010, 162(1): 145-151.

[41]Krassas G E, Poppe K, Glinoer D. Thyroid function and human reproductive health[J]. Endocrine Reviews, 2010, 31(5): 702-755.

[42]Qi Z Y, Shao C, Zhang X, et al. Exogenous and endogenous hormones in relation to glioma in women: a meta-analysis of 11 case-control studies[J]. PloS One, 2013, 8(7): e68695.

[43]Peragallo Urrutia R, Coeytaux R R, McBroom A J, et al. Risk of acute thromboembolic events with oral contraceptive use: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2013, 122(2 Pt 1): 380-389.

[44]Fortunato R S, Ferreira A C F, Hecht F, et al. Sexual dimorphism and thyroid dysfunction: a matter of oxidative stress?[J]. The Journal of endocrinology, 2014, 221(2): R31-40.

[45]Burek C L, Rose N R. Autoimmune thyroiditis and ROS[J]. Autoimmunity Reviews, 2008, 7(7): 530-537.

[46]Ameziane-El-Hassani R, Boufraqech M, Lagente-Chevallier O, et al. Role of H2O2 in RET/PTC1 Chromosomal Rearrangement Produced by Ionizing Radiation in Human Thyroid Cells[J]. Cancer Research, 2010, 70(10): 4123-4132.

[47]Snell D M, Turner J M A. Sex Chromosome Effects on Male-Female Differences in Mammals[J]. Current biology: CB, 2018, 28(22): R1313-R1324.

[48]Jiang W, Zheng L, Xu L, et al. Association between FOXP3 gene polymorphisms and risk of differentiated thyroid cancer in Chinese Han population[J]. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, 2017, 31(5): e22104.